| Outbreak: Chicken Liver Campylobacter |

|---|

| Product: Chicken Livers |

| Investigation Start Date: 1/10/2014 |

| Location: Multi-state |

| Etiology: Campylobacter jejuni |

| Earliest known case onset date: 12/5/2013 |

| Latest case onset date: 12/24/2013 |

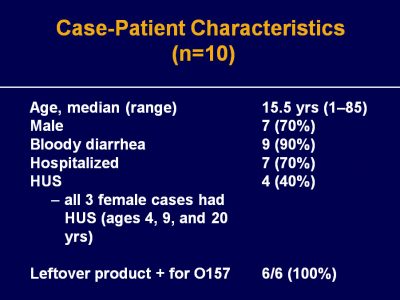

| Confirmed / Presumptive Case Counts: 4 / 2 |

| Positive Samples (Food): 5 |

| Outbreak Summary: |

|---|

| Six cases from three different states developed gastrointestinal illness after consuming under-cooked chicken livers. Most cases ate chicken liver made into pâté, but one case ate frozen raw chicken liver, based on her naturopath’s advice. All livers came from Draper Valley Farms in Washington State. |

| Details: |

|---|

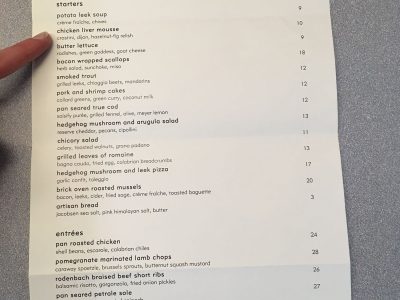

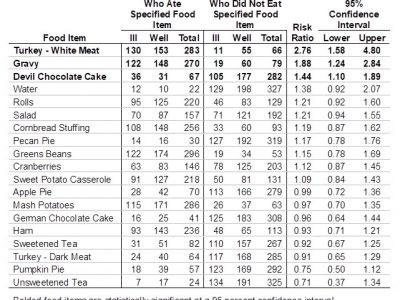

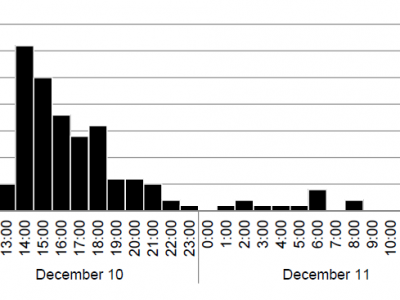

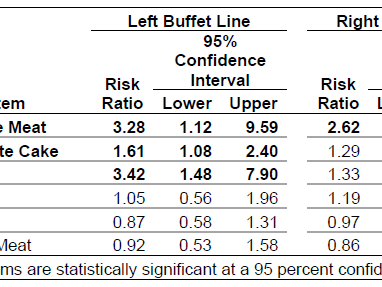

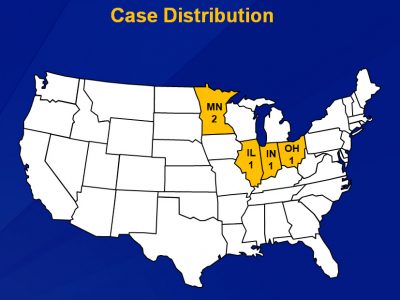

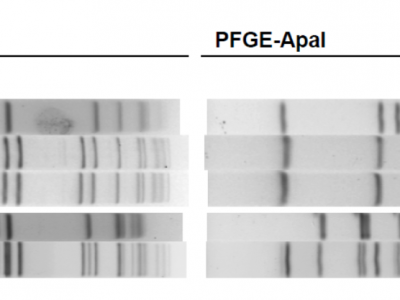

| Background On January 8, 2014, the Ohio Department of Health notified the Oregon Public Health Division (OPHD) of Campylobacter jejuni infections in two Ohio residents recently returned from Oregon. The couple had visited a Multnomah county resident, who had also become ill with campylobacteriosis. The three reported having dined together at Heathman restaurant in Portland. The only food shared by all three was chicken liver pot de crème, a dish similar to liver pâté. Pâté is a spreadable paste made from cooked poultry livers blended with scallions, butter, salt and other ingredients. All three cases became ill with vomiting and diarrhea within two hours of each other. On January 10, OPHD received additional reports of campylobacteriosis in two persons who had shared a chicken liver mousse appetizer at Wildwood restaurant in Portland. State epidemiologists launched an outbreak investigation. Methods In response to the reported illnesses, Multnomah County Environmental Health officials interviewed the restaurants to review food handling and preparation practices, and determine the source of the chicken livers served. Epidemiologists reached out to the Washington State Department of Health (WSDH) and discovered a recent case infected with C. jejuni who had eaten frozen, raw chicken livers as prescribed by a naturopathic doctor in the three days prior to illness onset. Using the reservation records from the Heathman, Oregon epidemiologists conducted a retrospective cohort study to find additional cases and to determine whether other foods could be causing illness. We reached 72 households whose residents ate at Heathman. In the households contacted, food histories were provided for 134 individuals. Results The environmental health investigation revealed that both implicated restaurants undercooked the chicken livers they served, and both received livers from the same distributor. State epidemiologists visited the distributor and found they only carried chicken livers from Draper Valley Farms, a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)-regulated facility in Washington State. Follow-up with the WSDH determined that their case also purchased her Draper Valley Farms chicken livers. Through the cohort study epidemiologists found seven individuals who reported having eaten chicken liver pot de crème at Heathman, one of which reported a campylobacteriosis-compatible illness (i.e., diarrhea lasting more than two days in the week after liver consumption). There was also one report of potentially compatible illness in a diner who did not report having eaten chicken livers. A presumptive case was defined as diarrhea lasting less than 2 days, within 7 days after consumption of undercooked chicken liver; a confirmed case was defined as laboratory evidence of C. jejuni infection within 7 days after consumption of undercooked chicken liver. Four laboratory-confirmed C. jejuni cases were reported in Ohio (1), Oregon (2), and Washington (1). Two presumptive cases were reported in Ohio (1) and Oregon (1). Only one human specimen from Oregon was available for subtyping at the Washington State Public Health Laboratory (WSPHL). Of nine Draper Valley liver samples tested for C jejuni, five were positive. Food samples culture positive for C. jejuni were sent to WSPHL for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) testing. The chicken liver samples from the Wildwood restaurant and the human specimen from the case that became ill after eating at Wildwood had indistinguishable PFGE patterns; no other PFGE patterns matched. Based on OPHD’s recommendation, both restaurants voluntarily stopped serving liver. Draper Valley Farms also reported they voluntarily stopped selling chicken livers. Lessons Learned Chicken livers are often contaminated with bacteria; if you’re going to eat them, make sure they are cooked thoroughly! In this outbreak, six cases of campylobacteriosis in Oregon, Washington, and Ohio were caused by consumption of undercooked chicken liver from a common supplier. No other common exposures were identified. A chicken liver sample and a human specimen had matching PFGE patterns. This is the second multistate outbreak of campylobacteriosis associated with consumption of undercooked chicken liver reported in the United States; in 2013 a similar outbreak occurred in Vermont. Chicken livers should be considered a risky food given the methods by which they are routinely prepared. Pâté made with chicken liver is often undercooked to preserve texture. It can be difficult to tell whether the livers in your pâté are cooked thoroughly because livers are often only partially cooked and then blended with other ingredients and chilled. A 2012 study2 found that 77 percent of chicken livers cultured were positive for Campylobacter. Washing chicken livers is insufficient to render them safe for consumption, as they can be contaminated internally and externally; therefore, cooking them to an internal temperature of 165°F is recommended. References 1. CDC. Multistate outbreak of Campylobacter jejuni infections associated with undercooked chicken livers--northeastern United States, 2012. MMWR 2013;62:874-6. 2. Noormohamed A, Fakhr MK. Incidence and antimicrobial resistance profiling of Campylobacter in retail chicken livers and gizzards. Food Path Dis 2012;9:617-24. |