| Outbreak: Angus Beef Patties |

|---|

| Product: Beef Patties |

| Investigation Start Date: 09/17/2007 |

| Location: Multi-state |

| Etiology: E. coli O157:H7 |

| Earliest known case onset date: 08/01/2007 |

| Latest case onset date: 10/08/2007 |

| Confirmed / Presumptive Case Counts: 47 / 0 |

| Positive Samples (Food): 17 |

| Outbreak Summary: |

|---|

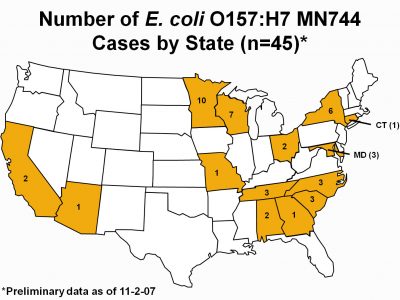

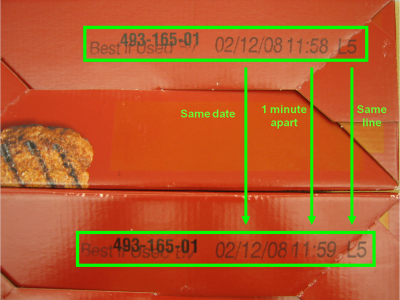

| Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) staff quickly identified the outbreak vehicle when the first four detected outbreak cases all reported consuming the same brand of premade beef patties. Investigators tracked down detailed product information from two cases, and two leftover boxes of beef patties obtained from case households were found to be produced on the same day and same production line in the same factor, literally produced within one minute of each other. Because of this link, MDH and the Minnesota Department of Agriculture issued a health alert and press release that day to notify the public of these findings before food testing results were available. Eleven outbreak cases were identified in Minnesota, including four cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), a life-threatening illness. This high percentage of HUS among cases of E. coli O157 infection suggests a particularly virulent strain of Shiga-toxigenic E. coli (STEC) or that cases ingested a heavy dose of bacteria. Thirty-six additional cases of E. coli O157 infection were identified from fourteen other states, as their bacterial specimen isolates yielded indistinguishable pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The outbreak PFGE strain of E. coli O157 was ultimately cultured from raw beef patties from all six boxes of product recovered from Minnesota outbreak case homes and tested by the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. This product appeared to be heavily contaminated – 13 of 13 subsamples taken from each box were positive. The outbreak strain of E. coli O157 was also isolated from implicated leftover food product collected from case homes in California, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. The rapid epidemiologic investigation (and the decision not to wait for food testing results or an unnecessary analytic study) undoubtedly prevented many additional cases, and may have prevented consumers from dying after consuming this product. |

| Details: |

|---|

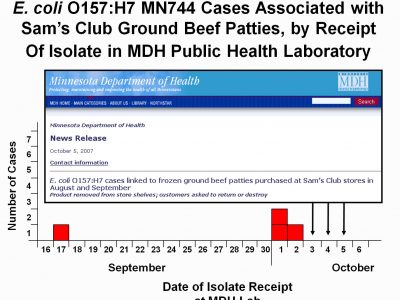

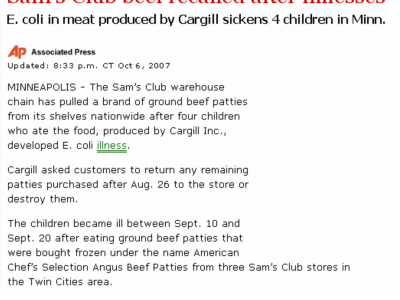

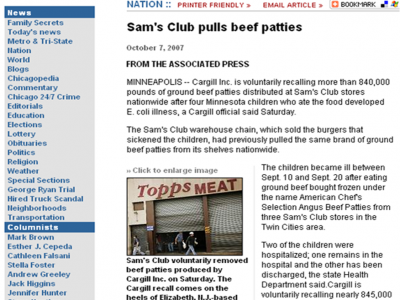

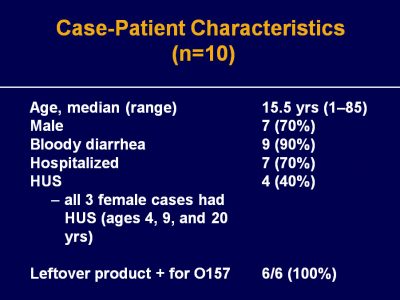

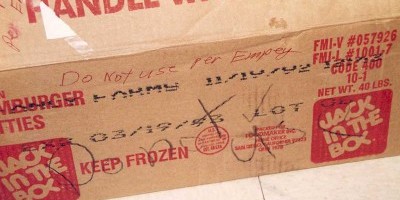

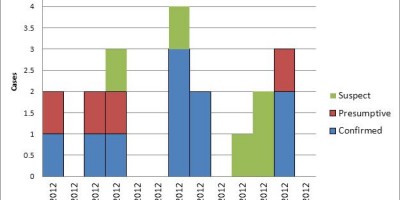

| Background On September 17, 2007, the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) was notified of a patient who presented to an emergency department with bloody diarrhea and was subsequently diagnosed with HUS. The patient had attended a large gathering and no other illnesses were reported from individuals who attended this event. On October 3, 2007, MSPHL identified two additional E. coli O157 isolates through routine surveillance with PFGE patterns that were indistinguishable the first case patient isolate. The first of these two new isolates was from the sibling of the first case and was considered to be a secondary infection (likely transmitted from one sick person to another). The second of these two new isolates came from a third patient who was unrelated to the previous two cases; this launched a local, and ultimately national, outbreak investigation. Methods Minnesota E. coli O157 cases were identified through routine surveillance of laboratory-confirmed cases of Shiga-toxigenic E. coli (such as E. coli O157:H7), active hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) surveillance, and foodborne illness complaint calls from the public. Phone interviews were conducted with all cases to collect information regarding symptom history and food exposures. Cases were asked to state where they shopped for groceries, and customer identification numbers were collected from consenting cases to obtain or verify food brand and purchase date information. When available, leftover ground beef patties or packaging were collected from case households. Information that was provided from packaging included product name, unit size, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) establishment number, the best-if-used-by (BIUB) date, the production line number, and the production time. The Minnesota Department of Agriculture (MDA) Laboratory tested each product submitted for the presence of E. coli O157 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and culture. If E. coli O157 was isolated, isolates were submitted to the MDH PHL for PFGE testing. Results A routine surveillance interview revealed that the first case had consumed a beef at a large gathering, three days prior to illness onset. The case reported that the beef was not fully cooked, having noticed that the middle of the patty was still pink. The source beef patties were premade and had been purchased at a local Sam’s Club store. No leftover product was available for testing, and the packaging had been discarded. The third identified case of E. coli O157 infection reported consumption of premade beef patties purchased from a Sam’s Club store. On October 4, 2007, MDH collected American Chef’s Selection Angus Beef Patties and packaging materials from the third case household and submitted the product to the MDA Laboratory for testing. Fortunately, production details which were printed on the bottom of the beef patty package; this helped regulators to understand more about when and where the beef patties were produced. Later that same day, MDH epidemiologists were notified of a fourth E. coli O157 case isolate with an indistinguishable PFGE pattern. This case was interviewed immediately and also reported consumption of the American Chef’s Selection Angus Beef Patties from Sam’s Club; investigators collected information from the beef patty packaging materials. The beef patties that the third and fourth case consumed were produced in the same facility on the same production line (L5) within one minute of each other (11:58 and 11:59). Because of this link, MDH and MDA issued a health alert and press release that day to notify the public of these findings. A recall of approximately 850,000 pounds of ground beef closely followed these alerts, announced by the United Stated Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) on October 6, 2007. Outbreak case identification continued after the press release had been issued. In total, eleven E. coli O157 cases were identified in Minnesota during the investigation. The median age was 19 years (range, 1 to 85 years) and seven (63%) cases were male. Onset dates ranged from September 10 to October 8, 2007. All cases had diarrhea, 10 (90%) had bloody diarrhea, seven (63%) were hospitalized, seven (63%) had abdominal pain or cramping, seven (63%) had fever, six (54%) had vomiting, and four (36%) developed HUS. The median duration of hospitalization for cases without HUS was 4 days (range, 3 to 4 days). For cases with HUS, the median duration of hospitalization was 21.5 days (range, 8 to > 60 days). All eleven E. coli O157 cases with isolates of the outbreak PFGE strain reported to the MDH during the investigation had consumed American Chef’s Selection Angus Beef Patties from Sam’s Club in the 7 days prior to illness onset. Of these, ten cases consumed the product grilled in patty form, and one case reported consuming the product slow-cooked in chili. The products were purchased from four different Sam’s Club locations, three of which were in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area. The implicated ground beef patties were packaged in boxes containing eighteen frozen, premade patties that each weighed 1/3 of a pound, for a total net weight of six pounds. Leftover product was collected from four other cases, for a total of six Minnesota case households. Of these six households, three had original beef patty packaging material available. Packaging material revealed that the three beef patty products were produced on the same day; all three had a BIUB date of 2/12/08. As discussed above, two of these products were produced on the same line (L5) within one minute of each other (11:58 and 11:59). The third product was produced on a different line (L6), but had a similar time stamp (11:57). All beef patty product samples collected from Minnesota case households were positive for the outbreak PFGE subtype of E. coli O157. No additional PFGE subtypes were isolated from the six product samples submitted from case households. Second enzyme PFGE testing revealed that all human and ground beef isolates were indistinguishable by the second enzyme as well. The outbreak subtype of E. coli O157 was also cultured from implicated ground beef by public health laboratories in California, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. There were 36 additional E. coli O157 isolates reported from 14 other states that had PFGE patterns indistinguishable from the outbreak subtype pattern. Onset dates for all patients nationwide ranged from August 1 to October 8, 2007. Two additional HUS cases were identified, both from Tennessee. Ten of the 20 (50%) cases from states other than Minnesota that reported consuming ground beef in the week prior to becoming ill specifically reported consuming the implicated product. Conclusions This was a multi-state outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 infections associated with the consumption of premade, frozen ground beef patties purchased from Sam’s Club outlets. Eleven cases were identified in Minnesota, including four cases of HUS. The investigation resulted in a recall of approximately 850,000 pounds of ground beef. Routine PFGE subtyping of E. coli O157 isolates combined with routine interviewing of cases, including detailed questions about consumption of ground beef (i.e., brand and purchase locations), enabled identification of the outbreak vehicle with a small number of cases. The type and brand of product was so specific that an analytic study was unnecessary, and interventions were implemented prior to laboratory confirmation of E. coli O157 in the food product. |