| Outbreak: Hip-hop Measles | |

|---|---|

| Product: N/A | Investigation Start Date: 5/27/2007 |

| Location: Lane County, Oregon | Etiology: Measles |

| Earliest known case onset date: 5/20/2007 | Latest case onset date: 6/5/2007 |

| Confirmed / Presumptive Case Count: 2 / 1 | Positive Environmental Samples: N/A |

| Hospitalizations: 2 | Deaths: 0 |

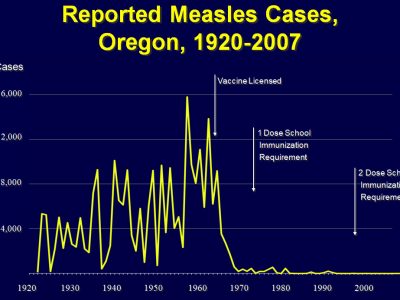

In 2007, two cases of measles detected in Oregon (both unvaccinated) led to an investigation of potential exposures within a hospital and the community at large. This investigation cost approximately $170,000 across local and state health departments, and the related medical system, highlighting the costs associated with measles contact investigation.

- • “Lessons Learned From A Measles Outbreak.” National Immunization Conference (NIC) Talk.

- • “Local Man Exposes Hospital To Measles.” The Register-Guard Newspaper, 2007.

- • “Eugene Man With Measles May Have Exposed Travelers.” The World Newspaper, 2007.

- • “Measles Victim Leaves House Despite Warning.” The Register-Guard Newspaper, 2007.

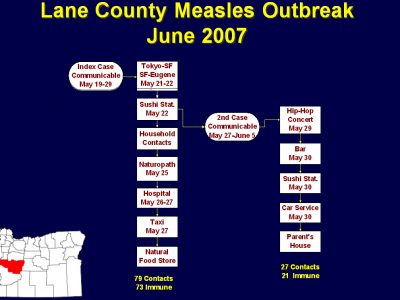

On May 27, 2007, Lane County Health and Human Services (LCHHS) received a report of a possible measles case admitted to a local hospital. The index case was in his twenties, unimmunized, and had been in Japan during his putative incubation period. A second case was identified later. The cases lived in a mid-sized urban community (pop. 200,000), and, as we were later to find out, had active social lives.

Hospital staff reviewed their employees’ immunization status and the airflow system. Measles cases and their exposed contacts were interviewed using Oregon’s standard measles case-report form. For those contacts lacking documentation of immunity, vaccine or immunoglobulin (IG) was offered. Instructions for voluntary quarantine were given to exposed non-immune contacts. The costs of containing the two measles cases was estimated for the hospital and local and state public health departments.

Public health recommendations included three tiers of contact investigation:

(1) Health-care workers (HCWs) in direct contact; patients in the waiting room and emergency department (ED); household contacts and close friends.

(2) HCWs in units potentially exposed via air flow.

(3) High-risk patients (pregnant moms, babies, immunocompromised) potentially exposed via air flow.

On May 31, 2007, Lane County officials confirmed the diagnosis of measles in the index case by polymerase chain reaction testing. His prodrome began on May 20. He flew on May 21 from Tokyo to San Francisco, and thence on May 22 to Eugene. His rash was first noted on May 25. He spent time at a local hospital ED and visited a health food store, naturopath and Japanese restaurant during his communicable period.

The patient was not given a mask while in the ED waiting for his initial evaluation; rather, he was placed in a regular airflow room and then wheeled through the hospital without a mask and ultimately put in a taxi for the ride home. Review of the hospital’s airflow system revealed that air from the ER (where case was housed but not isolated) was shared with the Coronary Care unit and Mother Baby Unit. The circulated air had a mixture of about 20% outside air and 80% recycled indoor air with 90%–95 % effective filtration and no HEPA filter.

During the investigation, the index patient refused to identify household contacts and did not respond to LCHHS phone calls, making contact investigation difficult. An unannounced home visit helped to clarify the situation and obtain new information.

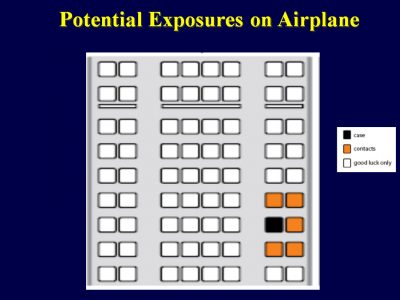

Information regarding 4 persons exposed on airline flights was not received until two weeks after the likely exposure. A week later, health officials were informed of two additional persons considered exposed, having sat next to or in front of the case, but phone numbers were not provided, and they had common last names. It also transpired that the case provided an incorrect seat number, and the model of the one of the airplanes was different from that listed on the airline’s website, further confusing attempts to identify exposed persons.

A second, unimmunized case, who had socialized with the index patient the night he arrived home from Japan, developed a febrile prodrome on May 30 and a rash consistent with measles on June 1. Koplik spots were visible. He declined lab testing.

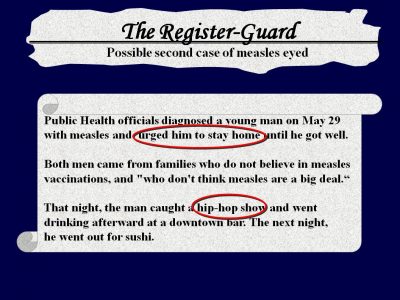

Although nurses advised case #2 to stay home to avoid spreading the disease, he went to public places. On May 29, the case caught a hip-hop show at a local concert hall, then to a downtown bar. The next night, he went out for sushi.

Three bands that played at the concert were on a national tour. During these shows, the attendees typically stand, dance and mingle, the band is on a stage just above the floor and the band members often venture into the audience. The band members were in Utah when they were notified about their possible exposure, and specimens to verify immunity were collected in Colorado. The testing was performed at CDC in Georgia, and after the tests proved negative they were vaccinated while performing in Iowa.

This investigation presented numerous challenges. Both measles patients came from families that did not believe in measles vaccination, and who “don’t think measles are a big deal.” Local public health officials’ recommendations for isolation and quarantine didn’t impede their pursuit of an active social life—which greatly increased the work of contact tracing. The following factors also complicated the response:

- 1. Exposures during multiple airplane flights

- 2. Delay in receipt of information about people exposed during travel

- 3. Exposures among a community of unimmunized peers

- 4. Delayed isolation of the case at the hospital

- 5. Shared ventilation between the case’s room and other hospital units

- 6. Lack of airborne precautions during transit through hospital at time of discharge

- 7. Withholding of information and non-compliance with voluntary home isolation

- 8. Limited documentation of measles immunity among healthcare workers

As a result, the investigation of these two measles cases and containment of the outbreak entailed substantial amounts of personnel time and money, as detailed below:

- • Hospital:

- – Incident Command System (ICS) activated

- – 1600 titers in a 2-week period

- – 97% of HCWs were immune

- – Cost of titers $40,000

- – 600 fit tested for N95 masks

- – 10 HCWs placed on furlough for several days

- – 3 HCWs furloughed for 21 days

- – 63 shots given

- – New policy requiring proof of measles immunity

- – Infection education module updated

- – Isolation & transferring process reviewed

- – $100,000 (estimated cost)

- • Local Health Department:

- – ICS activated

- – 2 cases

- – 168 contacts investigated

- – 90% were immune

- – 4 shots given

- – 4 people were placed in voluntary quarantine

- – $50,000 (estimated cost)

- • State Health Department:

- – ICS activated

- – $20,000 (estimated cost)

This outbreak was successfully controlled, despite the potential for spread. The limited extent of this outbreak, even in the setting of broad exposure, highlights the high level of population immunity achieved in Oregon and in other states.

This outbreak and its burden on clinical and public health resources could have been limited by adherence to recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for vaccination of high-risk adults against measles.

- • Consider using quarantine orders and the quarantine process as outlined in statute to minimize the risk of spreading the virus

- • Consider taking legal action when cases are do not comply with public health investigation and control efforts

- • Develop educational materials with clear, relevant messages targeting vaccine-hesitant communities affected by the outbreak

- • Continue efforts to ensure networking with the alternative medical community

- • Expand use of digital communications for public information

- • Ensure airborne infection control precautions in healthcare settings

- • Promote measles vaccination and documented evidence of immunity among healthcare workers in Oregon