| Outbreak: Hubbard Splash Fountain |

|---|

| Product: Splash Fountain in Hubbard, Oregon |

| Investigation Start Date: 7/25/2003 |

| Location: Marion County, Oregon |

| Etiology: Shigella sonnei |

| Earliest known case onset date: 7/16/2003 |

| Latest case onset date: 8/17/2003 |

| Confirmed / Presumptive Case Counts: 19 / 37 |

| Positive Samples: 0 |

| Outbreak Summary: |

|---|

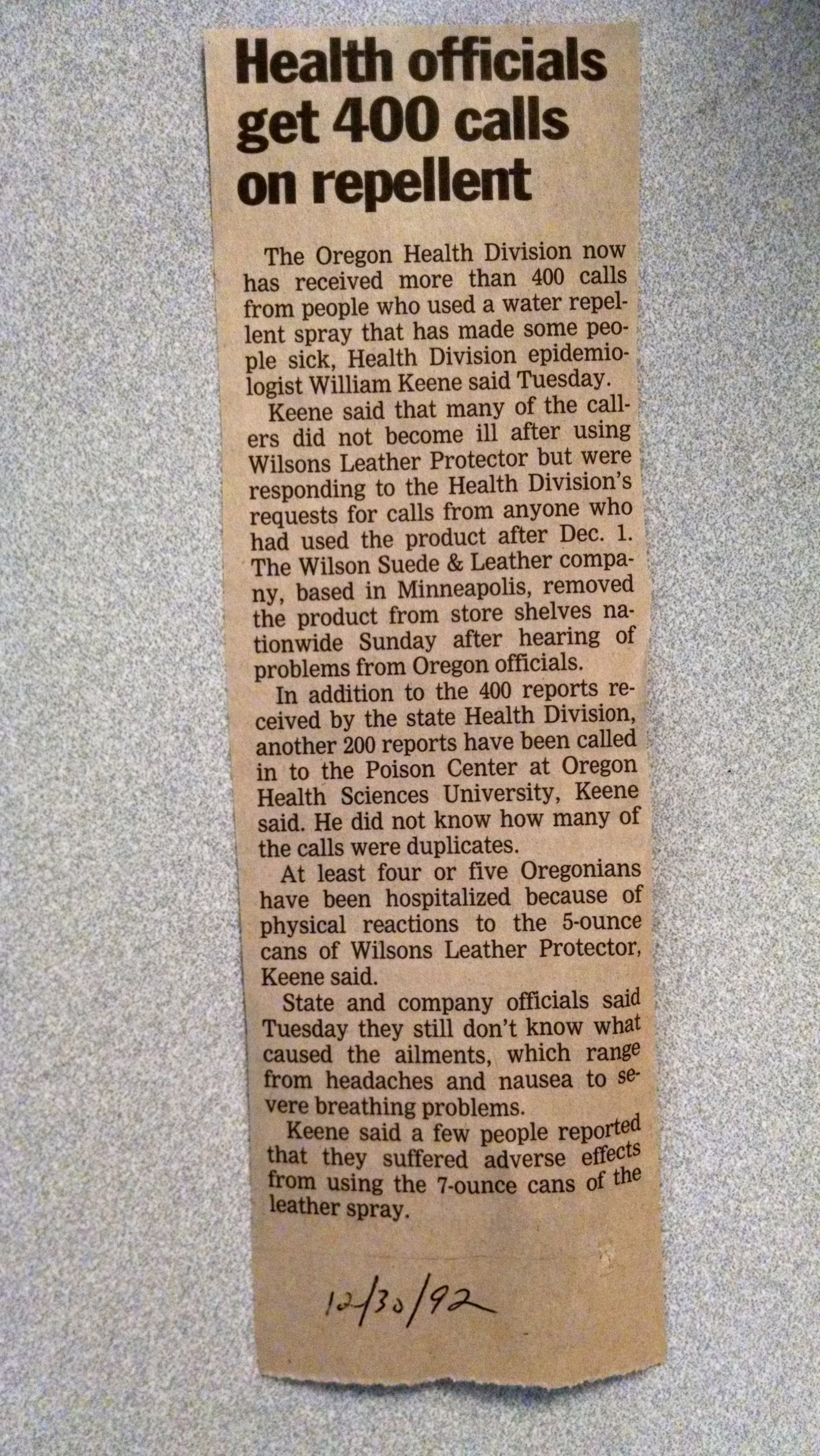

| Investigation of an outbreak of gastrointestinal illness erupted among children in a small community in Marion County, Oregon. Investigation by epidemiologists found that the illnesses were due to the fecal bacterium Shigella sonnei, and traced to an unusual common source: a splash fountain. This outbreak underscores the risk of large and prolonged outbreaks from these fountains and the need to develop and implement environmental health standards for their design and maintenance. Documents

Media Coverage |

| Details: |

|---|

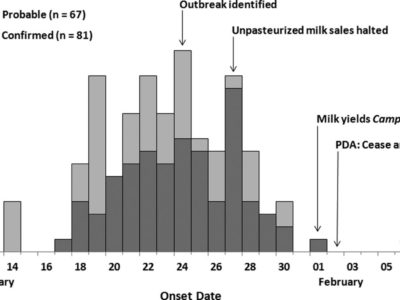

| Introduction On July 25, 2003, a physician notified the Oregon Public Health Division about 5 unrelated children with diarrhea. Epidemiologists began investigating to ascertain the bacterial etiology and the means of transmission, so as to institute control measures. Methods Confirmed cases had S. sonnei infections with matching DNA patterns by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), with illness onset date during July–August 2003. Presumptive cases had dysentery or diarrhea with fever and were epidemiologically linked to a confirmed case. Primary cases were the first ill in a household or daycare group. To identify the source of the outbreak, epidemiologists conducted a case-control study, using the first seven confirmed primary cases. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish with cases or household proxies. Respondents were asked about activities in which they had participated and places at which they had eaten during the last two weeks of July. Fifteen control children, matched to cases by telephone prefix and loosely by age (e.g., being less than 15 years old), were identified by systematic calling. To estimate an attack rate, epidemiologists conducted a telephone survey of 147 children drawn at random from the rosters of two local elementary (grades K–5) schools. Water samples collected from the fountain’s sump tank and surge tank, and from a nearby drinking water fountain, were assayed for fecal coliforms, E. coli, pH, and free chlorine. They were also tested for Shigella by membrane filtration and plating on salmonella-shigella agar. Shigella isolates were then speciated and subtyped by PFGE. Results Initial interviews identified no obvious common foods, but revealed that many cases had attended a festival in the city park (now known as Rivenes Park) of Hubbard, Oregon. All 7 cases but only 1 of 15 controls had played in the park’s interactive fountain (matched OR undefined, P=0.001). Through case reporting and the subsequent survey, investigators identified 19 confirmed and 37 presumptive cases associated with the fountain. Primary cases were exposed during at least a 10-day period ending August 1, when the fountain was closed. The fountain was a shallow basin about 8 meters in diameter with recessed spray nozzles that encouraged recreational interaction. The water drained to a central reservoir, which allowed standing water to accumulate and did not allow it to recirculate when the fountain was shut off at night. The surge tank was underground with a large device for straining out larger items like soda cans. Fresh water was supplied through a backflow device installed below ground level; the design did not provide adequate protection of the water supply from contamination. The filtration system did not have influent and effluent gauges, nor was there a flow meter. Chlorine was added manually by tossing "tri-chlor" (trichloro-S-triazinetrione) tablets into the surge tank on an irregular basis. The ultraviolet light ozone generator was too small for the flow rate, and the bulb had never been changed. Two water samples yielded fecal coliforms (940 and 370 per 100 mL, respectively) and E. coli (500 and 140 per 100 mL). Chlorine was not detectable. Of the 147 local children surveyed, 51 (35%) had played in the fountain during the last two weeks of July. Of the 51, 20 (39%) subsequently developed diarrhea (compared with 3% of those who had not visited the fountain [P<0.001]). Investigators estimated that, including children from other schools, older persons, and those who may have contracted the illness from secondary person-to-person spread, >500 persons most likely contracted shigellosis in this outbreak. Lessons learned/historical significance This splash fountain outbreak provides two unique lessons. First, it is a reminder for epidemiologists to remain objective when investigating outbreaks and not to presume foodborne transmission when dealing with outbreaks of enteric disease. Mark Twain said, “To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” but epidemiologists need to maintain a broader perspective. Second, this outbreak highlights the need for public health policy that addresses risks posed by the built environment. It underscores the risk of large and prolonged outbreaks from such fountains and the need to develop and to enforce standards for their design and maintenance. In 2003, the regulations and licensure regarding splash fountains were still being developed. After the outbreak, the state health department’s food, pool and lodging program visited and scrutinized the fountain and suggested that it be licensed and regulated as a public wading pool. The fountain was subsequently re-engineered and now has an automatic chlorinator. |